Beyond the IDE: Second-Generation AI Coding Software

Engineering teams are experiencing one of the fastest shifts in tooling since the rise of modern IDEs and cloud development.

AI coding software tools have moved far beyond autocomplete—developers can now describe intent in natural language and watch fully formed implementations appear. This creates a new foundation for productivity, creativity, and learning across engineering organizations.

For many teams, this rapid evolution is redefining how engineers work, moving from manual, line-by-line implementation toward higher-level collaboration with AI. Teams are now spending more time shaping logic, architecture, and outcomes, unlocking capacity for ambitious technical work that was once out of reach. As AI-assisted coding software evolves, it’s changing how organizations onboard, collaborate, and approach software design.

That’s why understanding their trajectory is essential for modern organizations. This article explores how first- and second-generation AI coding software emerged, what makes this moment transformational, and what the future may hold as intelligence becomes deeply integrated into the development workflow.

Why engineering is entering a golden age of AI-assisted coding

For decades, improvements in developer productivity largely came from better abstractions and faster feedback loops: higher-level languages, smarter IDEs, automated testing, and CI/CD pipelines.

AI-assisted coding software represents a different kind of leap. Instead of optimizing individual steps, it changes how developers interact with the act of building software altogether.

Second-gen AI software is shifting the developer experience away from manual keystrokes and toward intent-driven collaboration with intelligent agents. About 78% of professional developers now use AI tools in their development process, with 51% using them daily, indicating that AI-assisted workflows have moved from experimentation to essential practice.

Engineers now lead with intent—describing what they want a piece of software to do, its behavior, constraints, or shape, rather than worrying about the exact syntax needed to express it. The AI handles much of the mechanical translation, allowing developers to stay focused on higher-level thinking.

This reduction in cognitive overhead is especially valuable in complex environments. When engineers spend less time recalling APIs, navigating boilerplate, or digging through unfamiliar files, they can devote more attention to architecture, exploration, and problem-solving. Over time, this compounds into faster learning, clearer decision-making, and more confident iteration.

Enterprise teams stand to gain outsized benefits from this shift. Large, multi-repo codebases and legacy-heavy systems often slow teams down. The changes aren’t inherently difficult, but understanding context takes time. AI-assisted workflows help lower that barrier. Engineers find it far easier to contribute meaningfully without years of institutional knowledge and work in parts of the codebase that used to feel too risky or complex to touch.

The pace of these changes suggests something deeper than incremental efficiency gains. Compared to previous stages of development that took years—even decades—to mature, AI coding tools have compressed evolution timelines to months. What used to require multiple generations of tooling now unfolds within a single release cycle.

This acceleration marks a fundamental shift in how teams work. Engineering productivity is moving toward an intelligence-driven model—one where understanding, exploration, and creation are increasingly supported by systems that adapt to how developers think and work.

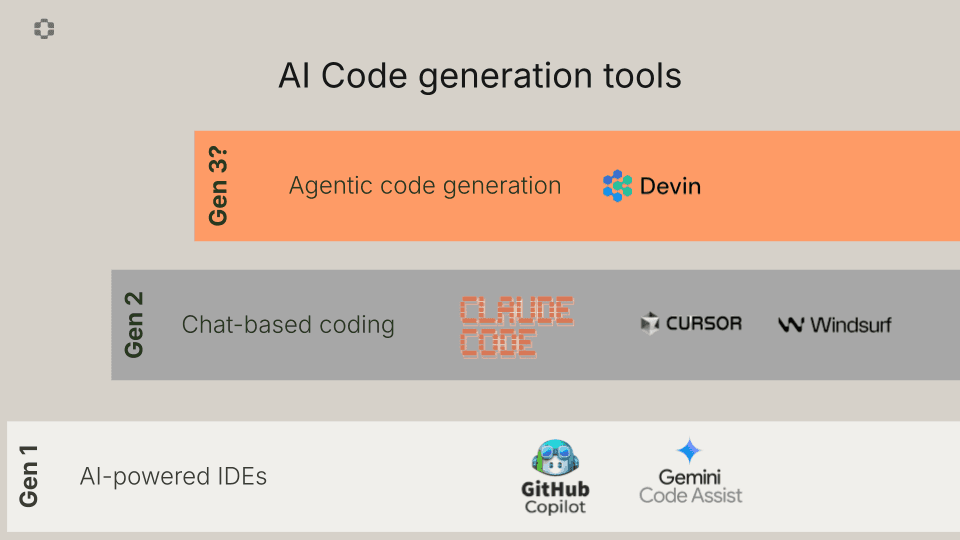

How first-generation AI coding software reshaped the development experience

The first wave of AI coding software, like GitHub Copilot, brought statistical intelligence directly into the IDE. Copilots learned from vast code corpora to predict what developers were likely to type next, offering context-aware suggestions, autocomplete, and boilerplate generation in real time.

For many teams, this immediately reduced friction at the start of work. Tasks like scaffolding tests, wiring up standard patterns, or writing repetitive structures became faster and more consistent. Developers no longer had to context-switch as often or search documentation for familiar patterns—they could stay in flow and move forward.

These tools also played an important role in leveling the field. Junior developers ramped up faster by seeing examples inline as they worked, while senior engineers reclaimed time previously spent on mechanical tasks. Over time, first-gen AI coding software nudged teams toward cleaner, more standardized code by reinforcing common idioms and safer defaults.

Still, their scope is clear. First-gen copilots enhance existing IDE-centric workflows rather than redefining them. They accelerate execution, but they don’t fundamentally change how developers express intent or reason about systems. The developer still leads with code; AI simply makes writing that code faster and more convenient.

First-gen software hasn’t gone away. Tools like GitHub Copilot remain widely used and valuable—they've become table stakes, complemented by a fundamentally different approach. That distinction matters, because it set the stage for what came next.

How second-generation AI coding software unlocked agentic coding

Coming fast on the heels of the first generation of tools, the second-gen AI coding software represents a more fundamental shift than simply making developers faster at writing code. Instead of optimizing keystrokes inside the IDE, these tools introduce agentic workflows that change how developers express intent in the first place.

Leading tools like Cursor, Replit, and Claude Code introduced chat-driven coding workflows, where developers describe desired behavior in natural language and the agent applies changes directly to the codebase. Rather than thinking in terms of individual lines or functions, engineers can operate at a higher level—asking for a feature to be implemented, a section of logic to be refactored, or an unfamiliar module to be explained.

This approach maps closely to the creative, “building up” process of software development. Engineers typically start with a mental model of how something should work, refine that vision through iteration, and then translate it into implementation. Agentic coding aligns with this flow by allowing developers to stay in that conceptual space longer, offloading much of the mechanical translation to the AI.

The impact is especially visible during early exploration and iteration. Prototyping becomes faster, refactors feel less daunting, and developers can experiment more freely without the same upfront investment in understanding every detail of a codebase. For teams working in large or mature systems, conversational interaction also makes it easier to navigate unfamiliar areas. Instead of manually tracing through files, developers can ask targeted questions and receive contextual explanations that accelerate learning.

Importantly, today’s second-gen software is intentionally scoped to the workspace. Their intelligence is anchored to the current repository and its surrounding context, allowing them to deliver fast, high-quality generation where developers spend most of their time working. This focus enables fluid, responsive interactions that feel like an extension of the developer’s own thought process.

By design, these tools prioritize creation over reasoning across every service, environment, or historical signal in a large distributed system. They are optimized to help developers move from intent to implementation quickly and confidently inside the workspace, rather than modeling an entire system end-to-end.

These boundaries reflect deliberate product choices, not shortcomings. 70% of developers using AI agents have reduced time on specific development tasks, underscoring the value of this targeted, contextual intelligence.

Second-gen AI coding software was built to make AI-assisted coding feel natural and productive, and in doing so, they’ve reshaped expectations for how intelligent assistance should show up in the development workflow. That shift toward faster learning, higher-level expression, and more fluid creation naturally sets the stage for how these tools may continue to evolve.

What second-generation AI coding software reveals about the future—and the possibilities of a third generation

As second-gen tools become part of everyday development work, they change what developers expect from intelligent assistance more broadly. Once engineers experience how fluid it feels to express intent, iterate quickly, and learn through conversation, it’s natural for those expectations to extend beyond individual files or workflows.

Agentic coding accelerates prototyping and learning in ways that were difficult to imagine just a few years ago. Developers can move faster from idea to implementation, explore unfamiliar areas of a codebase with confidence, and refine designs through rapid iteration.

The next step in the evolution of AI coding software is likely to be agentic coding tools that act as semi-autonomous software developers. Companies like Cognition and their agentic software engineer, “Devin,” may well represent this chapter, accelerating the move to implementation by planning, executing, and iterating across complete features.

Yet, even as these tools grow more capable at generating code, they remain focused on creation within the workspace. This focus reveals where the next layer of AI intelligence is taking shape.

The gap in today's AI coding tools

Over time, the positive experiences with AI coding software create a pull toward deeper forms of support—support that helps engineers reason not just about how code is written, but how it behaves and evolves within larger systems.

This creates a natural opening for tools that can reason about software as it runs, not just as it’s written. These tools would complement existing code-generation tools with broader, system-wide intelligence, extending today’s agentic workflows into areas such as architectural understanding and long-term impact.

In practice, that might mean tools that can comprehend relationships across multiple repositories, surface architectural dependencies, or incorporate signals from telemetry, logs, and user behavior. It could also include awareness of regression history and the rationale behind past decisions, helping teams understand not only what the system does today, but how it arrived there.

Say you described a feature request. These tools would not only generate code but also show how that change might affect database load or API latency based on historical patterns in your telemetry.

With this kind of intelligence, future tools may help teams reason about how changes ripple across systems before they are implemented. The goal wouldn’t be to slow developers down, but to preserve the creative flow enabled by second-gen software while adding confidence and clarity around downstream effects.

Taken together, these possibilities point toward AI companions that support both the creative and analytical dimensions of software development.

Rather than replacing the speed and expressiveness developers value today, a third generation could build on those strengths—extending intelligent support from individual workspaces into a richer understanding of complex, evolving systems.

How today’s software elevates engineering organizations—and early signs of deeper integration to come

Beyond individual productivity gains, second-gen AI coding software is beginning to influence how engineering organizations operate as a whole. One of the most immediate impacts shows up in onboarding. Conversational interaction makes large, unfamiliar codebases easier to explore, helping new engineers build context faster without relying entirely on documentation or institutional knowledge.

As developers become more comfortable working alongside agentic tools, the nature of their work also shifts. Less time is spent on boilerplate, repetitive edits, or mechanical implementation tasks, and more time is directed toward architectural decisions, system design, and thoughtful review.

Early evidence suggests this rebalancing is taking hold: 52% of developers agree that AI coding software has increased their productivity, allowing them to focus on the work that benefits most from human judgment and experience.

Code quality tends to improve as well. AI assistance reinforces consistent patterns, surfaces opportunities for cleaner abstractions, and reduces the cognitive load of navigating complex or unfamiliar areas of a codebase. Over time, this contributes to more maintainable systems and shared standards across teams, even as organizations scale.

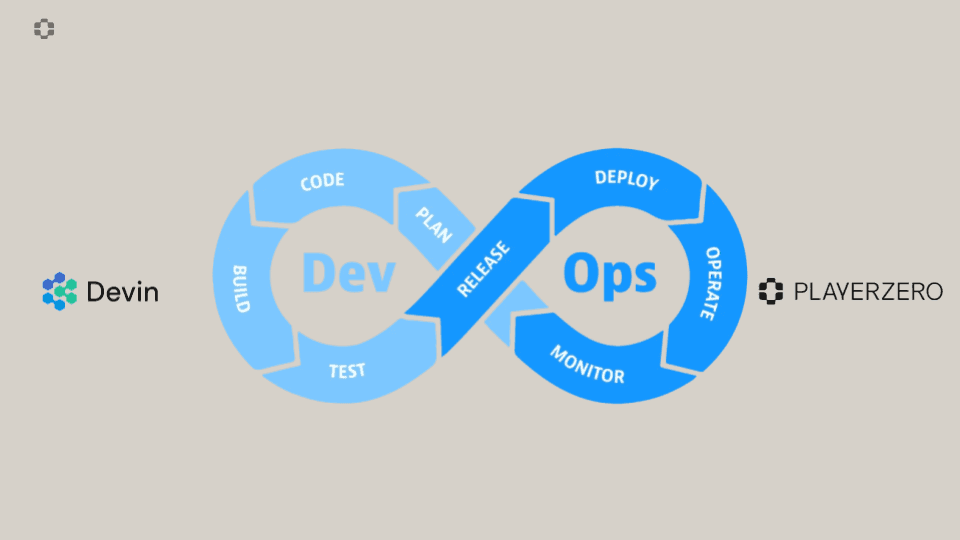

As these workflows mature, early signals suggest a broader direction the ecosystem may be moving toward. Some emerging platforms, including PlayerZero, are designed to complement today’s AI coding software. Connecting code generation intelligence with deeper system context—runtime telemetry, organizational knowledge, and real-world signals from how software is used—surfaces how changes affect system behavior in production. The intent is not to replace agentic coding, but to extend its benefits by grounding creation in a richer understanding of how systems behave over time.

Together, these trends point toward a future where intelligent tooling supports engineers not just at the moment of writing code, but across the full lifecycle of learning, collaboration, and system evolution—helping organizations grow without sacrificing clarity or momentum.

Navigating the next chapter of AI-assisted development

As AI-assisted code generation software becomes a core part of daily workflows, the most effective engineering leaders will treat them as foundational to their development strategy—not as side experiments or isolated productivity boosts.

In practice, that starts with encouraging thoughtful experimentation. Teams benefit most when second-gen tools are adopted in ways that fit their workload, codebase complexity, and engineering culture, rather than through blanket mandates. Leaders can support this by creating space for engineers to explore where agentic workflows meaningfully accelerate learning, iteration, and design.

Long-term gains also depend on pairing AI tooling with strong fundamentals. Clear documentation, architectural clarity, and shared learning practices help ensure that faster creation doesn’t come at the expense of understanding.

As teams observe how agentic tools reshape onboarding, collaboration, and decision-making, sharing those lessons across the organization becomes just as important as the tools themselves.

Ultimately, the next step is to stay curious.

Teams that continuously reflect on how AI-assisted workflows are changing their habits—and stay open to deeper forms of intelligent support as the ecosystem evolves—will be best positioned to build the next phase of AI-native software development, not just adapt to it.